JUST ECONOMIC POLICY IN TIMES OF AUSTERITY

(Manisha Weeraddana)

Tax Defaults in the Context of Austerity

Under the IMF framework the austerity toolkit comes as perhaps the most sought out solution. For countries in the Global South, including Sri Lanka, struggling with debt and overall macroeconomic instability this toolkit is considered a panacea. Within that context, when Sri Lanka turned to the IMF for the 17th time, a large part of the conditionalities (though not disclosed to the public transparently), revolve around raising government revenue through austerity measures. The idea of restructuring social security systems, restructuring the tax system as well as privatising underperforming government owned enterprises are exceedingly popularised by dominant Sri Lankan think tanks on popular media platforms is not surprising.

However, a major deficiency in Sri Lanka’s tax system, the tax collection and missing tax revenue, remains left out from the popular discourse. There is silence over conversations on tax defaults or tax arrears, as many of the defaulters are large corporate entities. In that spirit, this policy brief focuses on outlining one of Sri Lanka’s major perpetuators of budget deficits and government borrowings in a time where government expenditure and income take the centre stage.

Sri Lanka’s Escalating Tax Arrears: A Deepening Fiscal Concern

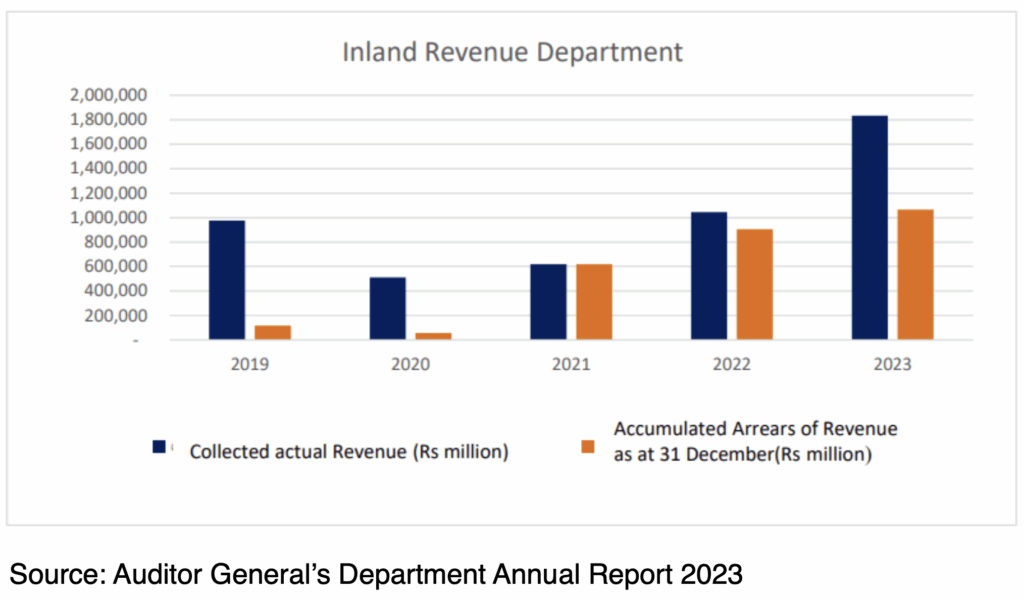

Sri Lanka has long struggled with rising tax arrears, a challenge that has significantly impacted the country’s fiscal stability. According to various audit reports on tax arrears by the auditor general these arrears have grown persistently, because of inefficiencies in both tax collection and enforcement contributing towards widening revenue deficits.

Since 2015 Sri Lanka was using a Legacy system, which was a mix between an automated and a manually maintained tax management system. In 2016, it was then replaced by the Revenue Administration Management Information System (RAMIS), a computer software, with a web portal which was opened to the general public in June 2015, hoping to minimise the inefficiencies within Sri Lanka’s tax management.

Regardless the attempt at improving efficiency RAMIS has not been able to significantly improve tax defaulting and inefficiencies in collecting these defaults. In fact, in auditing, the auditor general in ‘Second Report of the Committee on Ways and Means’ report highlights that technical bottlenecks in RAMIS, together with legal issues and management issues at the Inland Revenue Department, has further hindered self-assessment, upon which the Sri Lankan tax system is based on.

Tax Arrears in Recent Years

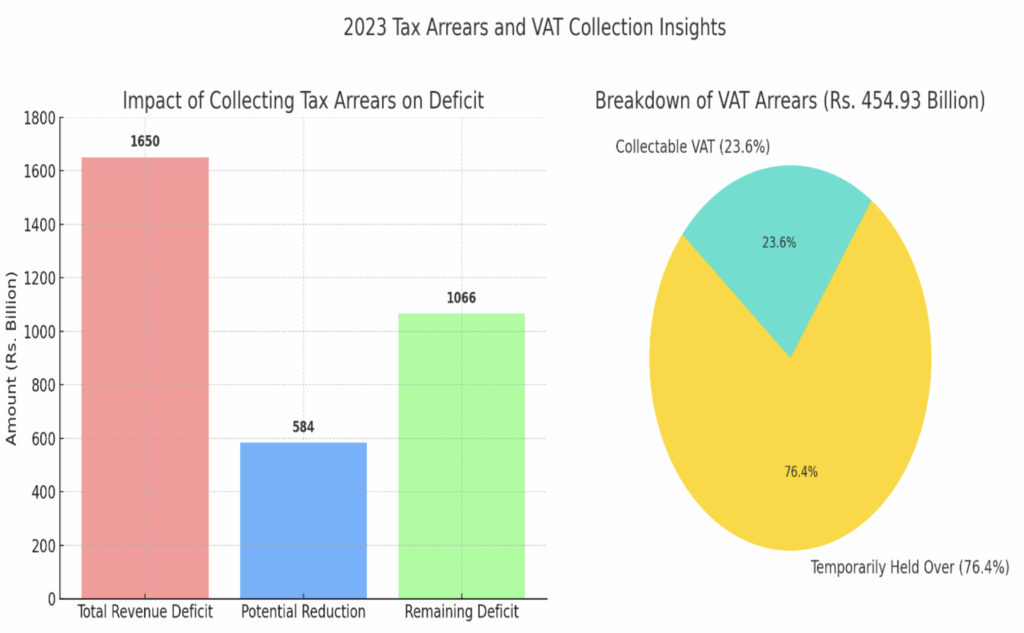

The total tax arrears increased from Rs. 579 billion (USD 1.93 bn) in 2019 to Rs. 1.066 trillion (USD 3.55 tn) in 2023, while the revenue deficit ballooned from Rs. 414 billion (USD 1.38 bn) to Rs. 1.65 trillion (USD 5.50 bn). Although full tax collection could have eliminated the deficit in 2019, its potential impact has declined, reducing the deficit by only 41.29% in 2023. This trend indicates that the deficit is expanding at a faster rate than tax arrears, further exposing inefficiencies in enforcement and collection.

VAT Revenue: Failure to Collect Taxes Already Paid by the General Public

Value Added Taxation (VAT) is a regressive tax system as the burden of income generation falls hardest on low-income groups. Yet, some 38% of total tax revenue in 2024 came from VAT, a 89.5 % increase from the previous year’s VAT income (Mid-year Fiscal Position Report, 2024). This hike in VAT revenue that came from the removal of tax exemptions of 100 items and increasing of the VAT threshold, took Sri Lanka’s VAT as a percentage of GDP increase up to 5% from being around 2.5% of GDP in 2023 (the lowest in South Asia at the time). However, as governments, specially under austerity measures, tends to look towards raising even regressive taxes such as VAT, it is essential to dive into the hidden costs surrounding the collection of such taxes. For example, in the case of VAT collections, The Auditor General’s reports , specifically the 2022 and the 2023, elaborates on failure to collect VAT incomes by the authorities in successive years. As of December 2022, VAT arrears and penalties accounted for Rs. 369 billion (1.23 billion USD) of the total Rs. 904 billion (3.01 billion USD) in tax arrears. Of this, Rs. 255 billion (0.85 billion USD) was temporarily suspended, while Rs. 114 billion (0.38 billion USD) —outstanding for nearly 13 years—was classified as recoverable (as per sources of the Department of Inland Revenue, 2024). A critical issue highlighted in the audit was that these unpaid taxes had already been collected by private and government entities from consumers as VAT but were never remitted to the government.

VAT defaults need more attention as:

a) it is a loss of government revenue that has to be financed mostly in terms of government debt;

b) it contains taxes paid for by the public but not collected by the authorities due to various failures in the system; and

c) VAT in nature are inflationary and thus a failure to collect such a tax is disastrous on the economy in many fronts, especially as it suggests both the public and the government are denied public revenue. In other words, corporate theft and corruption occurs at a cost to both the public and state coffers.

As of December 2022, VAT arrears and penalties accounted for Rs. 369 billion of the total Rs. 904 billion in tax arrears. Of this, Rs. 255 billion was temporarily suspended, while Rs. 114 billion—outstanding for nearly 13 years—was classified as recoverable. A critical issue highlighted in the audit was that these unpaid taxes had already been collected by private and government entities from consumers as VAT but were never remitted to the government.

Due to the Inland Revenue Department’s inefficiency in tax collection over five and a half years, the government permanently lost Rs. 22 billion (USD 0.07 bn) in VAT and penalty revenue—nearly 20% of recoverable VAT revenue. Further inefficiencies were noted in tax appeals, with 1,603 pending appeals amounting to Rs. 9 billion (USD 0.03 bn) remaining unresolved beyond the legally mandated period. If an appeal is not determined within the stipulated time, it is automatically deemed allowed, leading to further potential revenue losses. Additionally, inconsistencies in the Legacy System showed that 46 legal cases related to Rs. 296 million (USD 0.99 mn) in tax arrears were missing from official records.

A closer examination of 2023 data highlights that if the total tax arrears of Rs. 1.066 trillion (USD 3.55bn) had been successfully collected, the revenue deficit could have been reduced by Rs. 584 billion (USD 1.95bn)—equivalent to 35.39% of the total deficit. With respect to VAT, Rs. 454.93 billion (USD 1.52bn) was in arrears as of December 2023, of which Rs. 347.37 billion (USD 1.16bn) had been temporarily held over for various reasons. However, the remaining Rs. 107.55 billion (USD 358mn) in collectable VAT remained uncollected.

The recovery of defaulted tax happens to be time bound, as stated in the Amended VAT Act No. 15 of 2008; “The Commissioner General shall not initiate any legal proceedings under Sections 42, 43, 44 or 48 of the Act for recovery of defaulted tax when 5 years have expired under Section 37” . According to the auditor general reports for 2023, a large share of arrears not recovered can be attributed to the Department of Inland Revenue not being able to recover the dues within the stipulated time. In the case of VAT, such failures to recover taxes comes with an extra cost to the economy as such taxes concern taxes that have been already paid by the public to private sector companies – and never paid to the state coffers.

Tax Arrears, Revenue Shortfalls and impacts

Uncollected or defaulted tax revenues in turn mean a shortfall of government revenue. When the performances of tax revenues and tax arrears are analysed, the failure to raise sufficient funds to reduce the budget deficits annually appears as much as an issue of inefficiencies in tax collection. This market failure is much as an issue of having a narrow tax base, as the IMF points out in terms of government failure without due attention to comparable market failures.

As per the 2023 annual audit, the government was short of Rs. 1,650 billion (US$ 5.5 bn) in 2023 and Rs. 1,540 billion (5.1 bn) in the year 2022. In the past decade (2023-2013) the revenue deficit has been rising, except for 2016 and the deficit has been covered through local and foreign borrowing and different grants. With respect to these clear correlations between revenue shortfalls and rise in government borrowings, it would be helpful to look at how borrowings have risen in the recent decade while looking at the changes in revenue deficits in the same time period.

Domestic and foreign loans totalling Rs.32,791 billion (US$ 109.8 Bn) had been obtained from 2013-2023. When it comes to financing revenue shortfalls; the lowest recorded is 4.4 per cent while the largest is 45.59 per cent of revenue deficit. When the type of expenditure covered using these borrowings are concerned, 20.25 per cent of borrowings in the year 2019 and 19.65 per cent of borrowings in the year 2023 were used to settle recurring expenses. The highest portion of borrowings directed towards recurrent expenditure is in the year 2020 which is about 46 per cent. Thus, Sri Lanka’s lack of revenue collection has led to borrowing based consumption expenditure.

Inefficiencies and Systematic Failures

According to the Auditor General’s comments on key issues leading to inefficiencies in tax management and delays in the collection of tax arrears include several weaknesses.

These include:

- Limitations in the Revenue Administration Management Information System (RAMIS);

- The lengthy appeals process for disputed tax arrears and the absence of a dedicated tax judiciary, which makes legal recovery procedures slow and inefficient.

- Even with improvements to RAMIS at a cost to the government of Rs. 14,428 million (US$ 48.3 Mn), the Inland Revenue Department has failed to improve tax management and tax recovery.

Thus, the ongoing crisis in tax revenue collection underscores a series of systemic failures, including weak enforcement, administrative lapses, lack of transparency, and corporate miscreancy.

The failure to recover over Rs. 1.1 trillion (USD 3.67 bn) in defaulted taxes highlights the urgent need for comprehensive tax reforms. Strengthening tax compliance, enhancing enforcement mechanisms, and implementing more effective tax policies are critical to addressing Sri Lanka’s growing fiscal imbalance.

Without immediate intervention in tax management and recovery of defaulted revenue and delving into sever austerity measures, the country risks further financial instability. It risks exacerbating its already precarious economic situation, putting further pressure on the larger proportion of the general public, who have both already paid their taxes and have born the ill effects of consequent inflation due to hike in taxes, such as VAT.