In Sri Lanka, public policy lost in the neoliberal haze treats the market as a cure for all ills. Not only is the market omnipresent, but it is also omniscient and omnipotent. The charm of the ‘market’ that research and advocacy lobbyists are creating is so alluring that only a few wonder what abyss the neoliberal pied pipers are leading Sri Lanka into.

We have resorted to market solutions out of desperation. Starting from the Balance of Payment crises in the 1960s and 70s to ‘pani kuppi’ at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, to pyramid schemes in want of quick cash, to microfinance to drive financial inclusion and eradication of poverty, we have a plethora of experiences in seeking market-based solutions.

Walking at the edge of economic bankruptcy, we are also entertaining market-fostering surgical operations to transform failing State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) into thriving private enterprises with the hope of earning quick dollars. On the side lines, a few wonders where selling national assets will lead us. What are we going to sell next when everything sellable is sold? Is privatisation the correct strategy to take the Sri Lankan economy out of the crisis? What alternate policies should be adopted so that a second default and chronic dependence on debt can be averted?

This article invites the readers to revisit dominant narratives on the market and business. While historicising the dominant narratives on the market and industry along with the local and global examples, the article builds a case for repurposing the Sri Lankan State towards the mission of steering the economy out of the crisis. Economic theories and frameworks do not stand alone in the history.

They evolve and adapt to changing circumstances. The Internet and mobile phones, built through government-funded projects, offer a vast pool of knowledge and wisdom at our fingertips. So, we need not act as if we are trapped in a time capsule of a bygone era where information was scarce, and people lived in isolation and disconnected.

Markets work; govts don’t

Contrary to popular belief, markets cannot exist by themselves. They need to be created. From the point of creating necessary legal frameworks for the markets to exist, governments regulate them to ensure democratic control of the market. Government investments in technology, IT, medicine, and biotech have been fundamental to modern miracles like the Internet and the iPhone.

In times of crises, markets fail. Countless examples from the post-World War II, 9/11, the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 illustrate the proactive role played by the governments in resurrecting the markets. Governments built markets from scratch, injected extra cash into troubled industries, provided concessional loans and subsidies or simply bailed them out.

Governments from the US, the UK, and Sri Lanka used public money to correct the market failures even when the markets were at fault. The best example is the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. After the Easter Bomb attack in 2019, the Government of Sri Lanka provided concessional loans to exporters and hoteliers using public money. Yet, many evade or dodge tax payments. In that sense, markets are parasites seeking benefits and externalising social costs.

‘Trickle down’ is the common belief that justifies lower taxes to the corporate sector. Even though it’s proven wrong innumerable times, pro-corporate policymakers and research and advocacy lobbies still hold onto it. For example, the non-implementation of a tax on bondholders who did not participate in the Domestic Debt Optimisation (DDO) in Sri Lanka was commended by saying it would have become a ‘revenge tax’ and discourage investments.

An incalculable number of tax holidays and concessions given to BOI companies, big agribusinesses, and others in the corporate sector to encourage private sector-led growth in Sri Lanka for decades have not nurtured a robust private sector economy. In an article in the New York Times in 2010, Paul Krugman compared the belief in trickle-down to “old voodoo economics – the belief, refuted by study after study, that tax cuts pay for themselves.

” Instead of trickle-down, tax relief to the rich ‘vacuums up’ the income and wealth of the working people. Wealth segregation in the upper echelons of income groups is the outcome. The UNDP Report in 2023 identified Sri Lanka as one of the four Asian countries having the highest wealth inequality.

Markets are efficient; govts are not

‘Efficiency and productivity’ of the markets are another idea blown out of proportion by the market pundits. They forget that the markets are heterogeneous, differing from the goods and services they exchange. There are rice markets, shoe markets, toothpaste markets, fuel markets, education markets, health markets, organ trading markets and many more. Governments are better placed to provide some goods and services. For example, the government is the most efficient and productive provider of public goods and services such as health care, education, infrastructure, social security, energy, and R&D.

The Nobel Laureate economist Kenneth Arrow, in 1963, argued that private healthcare markets were inefficient due to uncertainty related to risks of illness and information. Adverse selection pushes the cost of health insurance up, excluding many who cannot afford to pay. According to OECD statistics, the per capita cost of health care is much lower and people are healthier in countries with a more significant government role in public health care services than in countries with private health care, such as the USA.

Free markets and perfect competition

The market is neither free nor perfectly competitive. Well-connected and big market players create information asymmetries that enable them to take advantage. The notorious Bond Scam in Sri Lanka is a good example. Cartels and oligopolistic control, hoarding and artificial scarcities, corporate lobbying, and shell companies are all about corporate corruption and market manipulations.

Apart from the bond scam, our day-to-day lived existences are heavily affected by corporate corruption. Take the sugar, cigarette, and forex scam at the height of the economic crisis. Even the immunoglobulin fraud unravelling. The private market players are equally at fault as the politicians involved. The same goes for privatising SOEs. Each privatising project, past and present, has involved significant corruption.

A creative and innovative government is crucial in a crisis, even for a market-led economy. A government that parrots enunciations of the multilateral lending institutions such as IMF and World Bank is at the risk of becoming a puppet of global and local capital and will end up deepening the crisis while killing the local economy.

In contrast, a visionary mission-oriented government will take swift actions to alleviate the pain of crisis on the public, nurture agriculture and local industries to ensure that the local economy will not suffer in the short and medium term, use SOEs efficiently and effectively to drive economic growth in the medium and long run. Instead of short-termism, a mission-oriented government will focus on the optimal use of resources while enhancing the capabilities of the State.

Mission-oriented govts

The history of governments (or states) illustrates how imaginative and creative governments have led the economy and society towards progress. Be it the US government in 1800 mired in a Civil War, in the aftermath of the Great Depression, Japan in the post-World War II, or poverty-stricken South Korea in the 1980s, or poverty-stricken Taiwan also faced with an existential crisis in 1950s or poverty-stricken China, or our own neighbour India, governments near and afar have shown that they have a central role in leading the economy forward. These governments, encountering their respective challenges, underwent radical transformations to deliver impressive outcomes.

They undertook high-risk investments in technology, infrastructure, manufacturing, and pharmaceutical industries while orienting business towards a social purpose through market regulations. Public agencies in Europe, Japan, Taiwan, China, Singapore, and South Korea, public banks in Europe and Germany, and multiple arms of the Department of Defence in the US (Defence Advanced Research Projects, CIA, US Navy) have been the bedrock of subsequent technological and manufacturing revolutions that these countries are known for. These breakthroughs functioned as stimulants for private businesses and were open to take advantage.

SL Developmental state and SOEs

The bold post-colonial State in Sri Lanka gearing national resources for innovation and change necessary to drive the industrial policy to advance development established SOEs in critical sectors of the economy. Mindful of the national sovereignty as a newly independent small State and accounting for the need for equitable development as a Third World country, foreign-held industries in energy and banks were nationalised. It was a with futuristic vision, courageous to withstand the risk of facing backlash from countries in the Global North which owned these industries.

SOEs have played a vital role, from fostering domestic industries while creating the domestic market to expanding electrification beyond income barriers and driving domestic production of textiles and manufactured goods. Even in their dilapidated form due to long-term neglect and purposeful undoing, SOEs remain valid and critical for post–crisis growth today. SOEs represent the necessary infrastructure that enables Sri Lanka to break free from debt dependency and move forward as an innovative and industrialised economy.

The market Pied Pipers argue that privatising SOEs will bring in quick dollars to finance the budget deficit. Privatising SOEs will appease the IMF and World Bank. While privatising SOEs would be the easiest, and most lazy public policy position that the government could assume, there are many other ways to lead market reforms and bridge budget deficits. SOEs should not be the scapegoats for lacklustre political leaders and unimaginative and mundane policymakers.

Privatising SOEs is a costly affair. Leave alone the cost of transforming SOEs into sellable enterprises and listing them in the Stock Market. The social cost, including the distributional cost of privatisation, is immense. For example, how long did it take the Ceylon Electricity Board to expand the electrification in Sri Lanka to include low-income households?

Tariff revisions over a few months have undone years of hard work by denying over 500,000 households their right to electricity. What is the social and distributional cost of 500,000 households going dark? Spillovers of denial of electricity to children, their education, and small and medium industries have a generational effect in regressing into history. Going back to the dark ages!

What reforms do the SOEs need? This is a valid question that we should mull over.

Political reforms should lead the way. It’s common knowledge that the use of SOEs as avenues to create employment for political clientele is at the root of the deterioration of SOEs. All the ministers holding public office since 1977 are guilty of overstaffing SOEs and appointing mediocre managers and CEOs. Not even a private business would survive such mismanagement. While creating employment opportunities is essential, it needs far-sighted approaches linked to the distribution of wealth, a better education system, and a balanced approach to the agriculture, manufacturing, and services sectors of the economy.

Organisational reforms should follow political reforms. Reorienting SOEs for their public purpose and holding the management accountable to the mandate of respective SOEs is essential. It could be harnessed with incentives to reward managers and employees for their contributions to enhance efficiency, productivity, and public service.

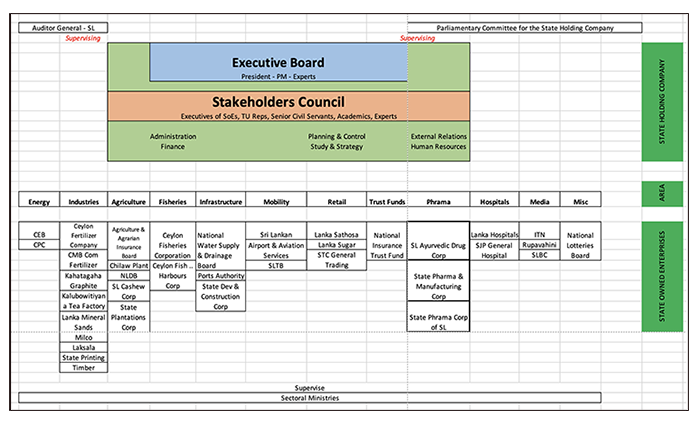

Create a mechanism to monitor SOEs. Ministerial oversight on SOEs as practised in Sri Lanka now is not working. Often, the Minister and the bureaucracy neither have the expertise nor information to supervise and monitor SOEs. As much as SOEs should generate quarterly and annual reports on their performance, the oversight agency should have the necessary skills to monitor and supervise them. Mariana Mazzucatto, influenced by examples from Italy, Spain, the UK, Sweden, and France, introduces the idea of a ‘State Holding Company’ as an overarching oversight agency to supervise and monitor SOEs.

To locate the idea in the SOE landscape in Sri Lanka would roughly be as follows: (See chart)

Rather than attempting to be prescriptive or to plant models from elsewhere, I want to expand the debate beyond the privatisation discourse. Democratic ownership and control of SOEs is not limited to Sri Lanka. It is a successful model which benefits the public, including private businesses. An entrepreneurial State could be the engine of growth, navigating society and the economy out of the crisis.